A SCULPTOR IS LIKE A WELL-BEHAVED CHILD WHO HAS BEEN TAUGHT NOT TO BREAK THINGSMoisès Villèlia, Cabrils 1960

This is a man whose shaping as an artist occurred, as he himself would say, as a result of having had a happy childhood. His whole childhood was structured in terms of a family environment which heightened his sense of the application of reason, strictness, the faculty of observation and a playful feeling for things.

His father was a great carver, with an extensive knowledge of different styles and a very strong ideological outlook. His mother had a musical training, like the other children in her family. One of her brothers became a good concert guitarist in Paris, but she did not turn professional. Villèlia studied at the Damon School, following the Montessori method, until the war cut short this rationalist education. Later he began to train as a carver in his father’s workshop. He was a person who learnt quickly –not only the technique of carving wood but also how to interpret different styles. In parallel with his development within the world of homo faber he explored the world of poetry on his own. |

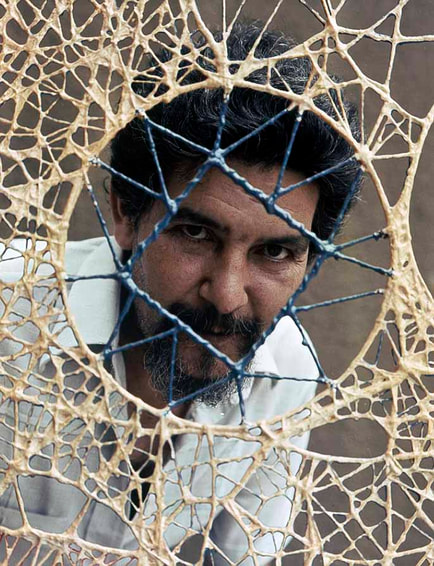

Villèlia

|

This brought him to a crossroads where he had to decide whether to go on developing by means of forms and materials or trough poetry. In the end he opted for forms and materials, and with them he developed a world of his own. His sculptures evolved towards a plastic conception which originated in Ángel Ferrant, Julio González, Alberto, and Russian Constructivism as transmitted by Naum Gabo.

A world of forms that gradually acquired a structure in his mind, with the aid of all his senses. It was his brain that enabled him to visualize them and, with his hands, make them a reality.

In this process it is understood that he looked back to his childhood, and in this reflection he gave importance to the fact that he had learnt his first letter, the letter P, in a tactile way, closing his eyes and feeling the shape of the letter on sandpaper with his fingers.

He realized that, if he wished to pursue the process of creation through form, he must understand materials and let them flow as if they had a life of their own.

He began to work with materials that the sea had eroded and plants and vegetables to which life had given shape.

His strolls on the beach became more frequent. He observed, and he collected the materials that he thought he understood and could allow to flow. He realized that, even though man had understood much of the language of clay, stone, iron, etc., there were still countless materials that man had not sought to understand with a view to creating with them.

This led to the series of materials eroded by the sea and the series of vegetables and plants, such as onion stalks, cabbage stems, grass, cork, and so on. His eagerness to learn increased more and more, and when asked about this he explained that it was “so as not to copy unconsciously”.

He had already found materials that he had been able to allow to flow, and he had created with them; but his sculptures were still very corporeal. He still had many references from his origins. He wished to go on evolving. Until then he had worked with materials in accordance with his training as a carver. In order to create he had to rough-hew, “removing matter”. Thus he achieved forms. He learnt to cut wood with gouges, chisels and burins, allowing for the fact that all tools must have an exit point when cutting, to avoid gigging into the wood. This led him to acquire a very great understanding of lines.

But he felt limited. He wanted to draw in space and connect up empty spaces. He did so by means of lacquered thread and wire. He went on thinking about new materials until he discovered reed cane.

A world of forms that gradually acquired a structure in his mind, with the aid of all his senses. It was his brain that enabled him to visualize them and, with his hands, make them a reality.

In this process it is understood that he looked back to his childhood, and in this reflection he gave importance to the fact that he had learnt his first letter, the letter P, in a tactile way, closing his eyes and feeling the shape of the letter on sandpaper with his fingers.

He realized that, if he wished to pursue the process of creation through form, he must understand materials and let them flow as if they had a life of their own.

He began to work with materials that the sea had eroded and plants and vegetables to which life had given shape.

His strolls on the beach became more frequent. He observed, and he collected the materials that he thought he understood and could allow to flow. He realized that, even though man had understood much of the language of clay, stone, iron, etc., there were still countless materials that man had not sought to understand with a view to creating with them.

This led to the series of materials eroded by the sea and the series of vegetables and plants, such as onion stalks, cabbage stems, grass, cork, and so on. His eagerness to learn increased more and more, and when asked about this he explained that it was “so as not to copy unconsciously”.

He had already found materials that he had been able to allow to flow, and he had created with them; but his sculptures were still very corporeal. He still had many references from his origins. He wished to go on evolving. Until then he had worked with materials in accordance with his training as a carver. In order to create he had to rough-hew, “removing matter”. Thus he achieved forms. He learnt to cut wood with gouges, chisels and burins, allowing for the fact that all tools must have an exit point when cutting, to avoid gigging into the wood. This led him to acquire a very great understanding of lines.

But he felt limited. He wanted to draw in space and connect up empty spaces. He did so by means of lacquered thread and wire. He went on thinking about new materials until he discovered reed cane.

|

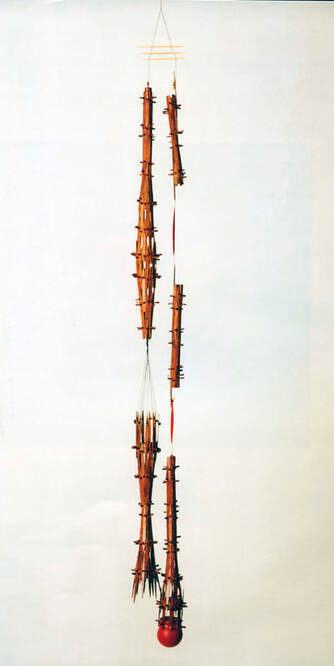

Sculpture of MNCARS collection

|

His bamboo language had begun.

He had found a material that was hollow inside and so provided him with an empty space and at the same time allowed him to include in it the threads and wired with which he had already experimented. He discovered the cane’s nodes and its elasticity, and the transformation it undergoes when it dries up, contracting and becoming deformed. He took advantage of those characteristics. With reed cane, wire, cork and toothpicks he started to create his great world of mobiles, which he continued developing throughout his life. Then he discovered Phyllostachys, a variety of bamboo with a structure similar to that of reed cane but with thicker walls and with the nodes further apart. With it he was able to give greater importance to the constructive sense of his works by means of pegs and splines. His personality as an artist and his ability to adapt his world to a multitude of disciplines led him, among other things, to direct and also design the scenery for Joan Brossa’s first play for the theatre, La jugada. Later he tried to understand new materials, such as concrete, asbestos cement and expanded polystyrene. He realized that their structure was man-made, rather than created by life, as was the case with most of the materials with which he had worked. |

In the case of concrete, he was able to create its structure, modifying it in terms of the type of cement, coloring and aggregate –which allowed him to vary not only its color but also its texture and resistance. He achieved shapes by means of molds or shuttering.

Tubes of asbestos cement, which have a hollow space like bamboo, enabled him to apply the knowledge that he had acquires with that material.. The empty space inside gave him the possibility of filling some parts of the tube with concrete and exploiting the interplay between the corporeality of concrete and asbestos cement and the empty spaces.

He used expanded polystyrene as “lost” shuttering for concrete. By creating empty spaces inside the concrete and then applying pyrography to the sheets of polystyrene, he was able to create concrete panels with a great variety of textures and colors in accordance with their composition.

The result of the study and understanding of these materials was the creation and construction of two gardens: the Pros Garden in Masnou and the La Ricarda Garden in the delta of the Llobregat.

In them he conceived a space that was sculptural and, above all, functional and playful. There were areas for moving around or staying still, places for children to play and so on. The sculptures made with tubes of asbestos cement, like the concrete ceiling lights, became partitions and also retaining walls. The spaces became sculptural.

In these gardens he also created sculptural games, such as the set of chess pieces made out of tubes of asbestos cement.

All his experiments with wire and metal rods also had their result in sculptures and stained-glass windows.

At this decisive point in his development he entered the world of industrial design, working with furniture, lamps and children’s games. Although it might seem that his conception of industrial design had its roots in Ruskin and Morris, as a result of his craft training, if we make a deeper analysis oh his designs and discourse we see that his Constructivist conception links up with the rationalism of Alver Aalto. When asked about this, he wrote: “ In order to be able to work in conjunction with industry, the designer must dispense with certain personal concepts. Artistic feelings can only be used as a historical reference of sensibility, and they must be adapted to formulas where the item is manufactured. As an artist, I have had the human need to contribute to the vast developing horizon that we might call “the humanization of forms”, the driving idea of that great sculptor Ángel Ferrant”.

In his designs for children he created constructive playful games in which there was no warlike concept. In some cases, they were wooden pieces that fitted together to create constructions; in another example he accentuated the feeling of collaboration between the two players, who had to move pieces of various shapes and sizes in order to occupy certain spaces. This was the case of the game El convivent (Companion).

His furniture for children originated from the same considerations. The child could use it as such, but could also create construccions with it.

In all his designs there is a balance between type of material, functional utility and aesthetic concept.

As for his drawings, we can say that in them his creative power developed extensively while he was living in Paris, perhaps owing to the circumstances – the lack of space.

On the one hand, we find drawings that were studies for sculptures in concrete, wire mesh or bamboo, some of which he produced later while in other cases he only used certain solutions relating to composition, balance or assembly.

On the other hand, his drawings began to acquire importance in themselves, as an exploration or forms on paper. Some of the works in these series of drawings were accompanied by poems. He created a series of books with drawings, poems and texts.

He observed that drawings always have a “rear part” which is overlooked, and began to cut paper and punch holes in it so that it could be seen on both sides and become a “whole”.

These techniques with paper gave rise to new series and various books.

Tubes of asbestos cement, which have a hollow space like bamboo, enabled him to apply the knowledge that he had acquires with that material.. The empty space inside gave him the possibility of filling some parts of the tube with concrete and exploiting the interplay between the corporeality of concrete and asbestos cement and the empty spaces.

He used expanded polystyrene as “lost” shuttering for concrete. By creating empty spaces inside the concrete and then applying pyrography to the sheets of polystyrene, he was able to create concrete panels with a great variety of textures and colors in accordance with their composition.

The result of the study and understanding of these materials was the creation and construction of two gardens: the Pros Garden in Masnou and the La Ricarda Garden in the delta of the Llobregat.

In them he conceived a space that was sculptural and, above all, functional and playful. There were areas for moving around or staying still, places for children to play and so on. The sculptures made with tubes of asbestos cement, like the concrete ceiling lights, became partitions and also retaining walls. The spaces became sculptural.

In these gardens he also created sculptural games, such as the set of chess pieces made out of tubes of asbestos cement.

All his experiments with wire and metal rods also had their result in sculptures and stained-glass windows.

At this decisive point in his development he entered the world of industrial design, working with furniture, lamps and children’s games. Although it might seem that his conception of industrial design had its roots in Ruskin and Morris, as a result of his craft training, if we make a deeper analysis oh his designs and discourse we see that his Constructivist conception links up with the rationalism of Alver Aalto. When asked about this, he wrote: “ In order to be able to work in conjunction with industry, the designer must dispense with certain personal concepts. Artistic feelings can only be used as a historical reference of sensibility, and they must be adapted to formulas where the item is manufactured. As an artist, I have had the human need to contribute to the vast developing horizon that we might call “the humanization of forms”, the driving idea of that great sculptor Ángel Ferrant”.

In his designs for children he created constructive playful games in which there was no warlike concept. In some cases, they were wooden pieces that fitted together to create constructions; in another example he accentuated the feeling of collaboration between the two players, who had to move pieces of various shapes and sizes in order to occupy certain spaces. This was the case of the game El convivent (Companion).

His furniture for children originated from the same considerations. The child could use it as such, but could also create construccions with it.

In all his designs there is a balance between type of material, functional utility and aesthetic concept.

As for his drawings, we can say that in them his creative power developed extensively while he was living in Paris, perhaps owing to the circumstances – the lack of space.

On the one hand, we find drawings that were studies for sculptures in concrete, wire mesh or bamboo, some of which he produced later while in other cases he only used certain solutions relating to composition, balance or assembly.

On the other hand, his drawings began to acquire importance in themselves, as an exploration or forms on paper. Some of the works in these series of drawings were accompanied by poems. He created a series of books with drawings, poems and texts.

He observed that drawings always have a “rear part” which is overlooked, and began to cut paper and punch holes in it so that it could be seen on both sides and become a “whole”.

These techniques with paper gave rise to new series and various books.

|

It was also during his stay in Paris, in 1967-68, that he developed his conception of punlic spaces in a series of maquettes for parks. When he was in Ecuador, from 1970 to 1972, he discovered Guadua bambusa and giant Dendrocalamus, which gave more grandiloquence to his sculpture. Guadua bambusa is s bsmboo with thick walls and short interno9des, while the nodes have a curious organic form. His way of working with it recalls the world of carving. Its proportions enabled him to make sculptures of large dimensions.

Of even greater size is giant Dendrocalamus. This bamboo has a structure similar to that of reed cane: in both cases, but in different proportions, there is a long distance between the nodes, which have a similar flat membrane. Consequently, he was able to develop the same conception as with reed cane but in dimensions that he had not been able to achieve with cane or other species of bamboo. Among the sculptures made in Guadua we find a series of pieces with plaster applied and with degradation of color. This series originated from a consignment of bamboo that arrived with cracks, which caused a change in its structure. Instead of discarding the consignment, he began to work with it and tried to understand it as if it were a new material. It was in order to cover the numerous cracks that he began to apply plaster. As he could not work with elasticity of the fibres, the sculptures became more corporeal. In some cases, I order to obtain elements with bends he incorporated pieces of Phyllostachys. |

Sculpture of IVAM's collection

|

Apart from all this, his knowledge of line led him to discover the secret language of the Quitu-Cara seals during his travels in Ecuador.

And so he went back to “cobwebs”, toothpicks and models of public areas. He also wrote a play, El artista, which is, above all, his testament for posterity.

Nahum Villèlia

This text forms part of the catalogue of the exhibition held at the Valencian Institute of Modern Art (IVAM, as abbreviated in Valencian) in 1999.

And so he went back to “cobwebs”, toothpicks and models of public areas. He also wrote a play, El artista, which is, above all, his testament for posterity.

Nahum Villèlia

This text forms part of the catalogue of the exhibition held at the Valencian Institute of Modern Art (IVAM, as abbreviated in Valencian) in 1999.